New gas infrastructure for the European Union: is common sense prevailing?

The European Union wants to increase its fossil gas import capacities

« Common sense prevailed », according to Lars Ole Løcke, the spokesperson for the European People’s Party. On February 12th, the European Parliament rejected a motion by the Greens which questioned the « fossil » content of the 4th list of Projects of Common Interest. This makes 27 gas pipelines and 5 liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminals1 eligible to receive European subsidies or loans from the European Investment Bank2.

Among the 27 pipelines, 4 would be used to import natural gas from outside the European Union (EU). This is the case, for example, of the EastMed project, which aims to transport natural gas from offshore deposits in the eastern Mediterranean to Greece, Italy and central Europe. Another important project, because of its length, is the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline, which links Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan to the EU via Georgia and Turkey.

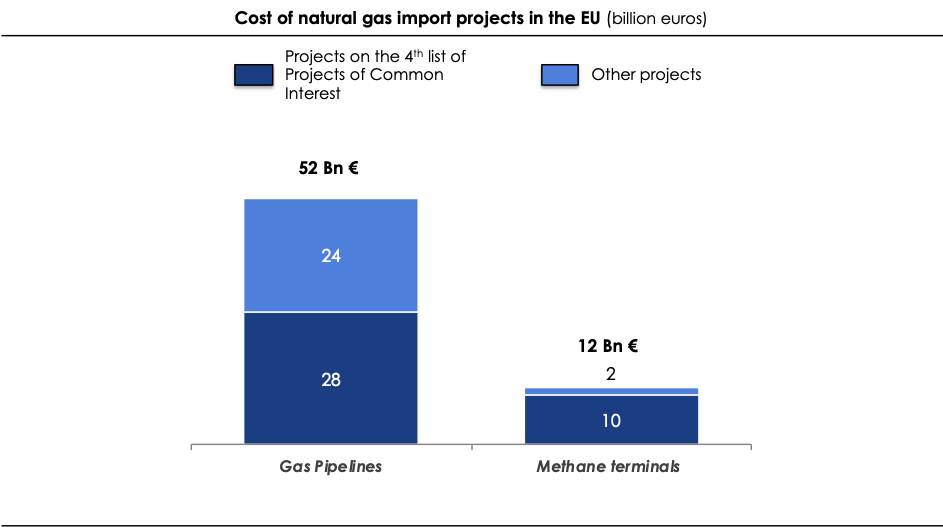

Beyond the list of projects of common interest selected by the Commission, the inventory carried out by the Global Energy Monitor3 shows that the overall cost of projects intended to import natural gas into the EU amounts to 64 billion €, including 52 billion in gas pipelines and 12 billion in LNG import terminals. 54% of the gas pipelines and 9% of the LNG import terminals (in terms of capacity) are already under construction, while the other projects are still under study.

Source: M. Inman, 2020

It should be noted that these investments represent new installations and not the renewal of existing infrastructure. According to the Gas at crossroads study of the Global Energy Monitor network, the projects would represent an increase in annual import capacity of 138 billion cubic meters of natural gas for pipelines and 95 billion cubic meters of natural gas for LNG import terminals, that is to say a 30% increase compared to existing installations.

Three background elements

To better understand the ins and outs of these figures and of the European Parliament’s decision, let us recall three elements of context:

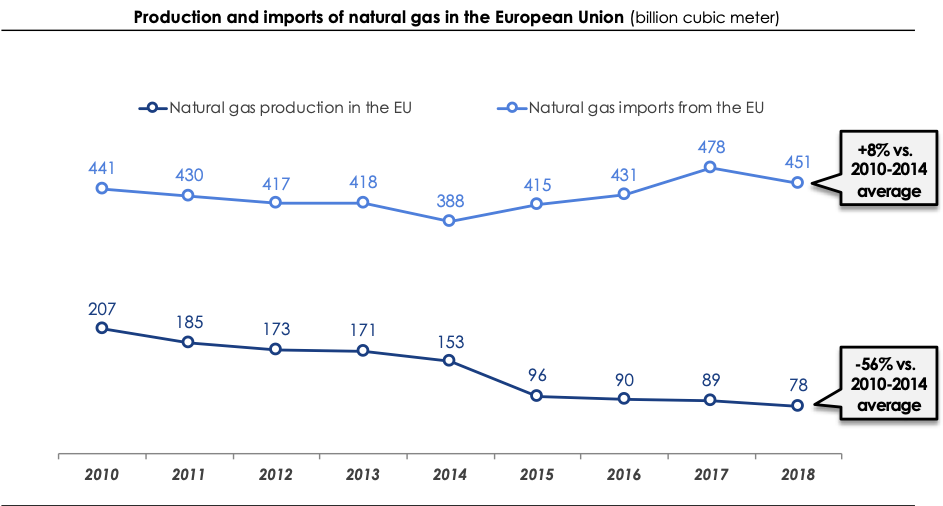

1. The European Union is producing less and less natural gas on its soil and compensates for this by increased imports. The drop in absolute production (-129 bcm5 between 2010 and 2018) is, to a large extent, offset by the increase in imports (+103 bcm between 2010 and 2018).

Source : Eurostat, 2020

With the exception of the United Kingdom, which accounts for 36% of EU production in 2019 and whose production increased by 4% between 2014 and 2019, all the other significant6 producing countries have seen their production levels fall between 2014 and 2019 In particular the Netherlands, which fell by 52% over the period, Romania (-11%), Germany (-44%) and Poland (-7%).

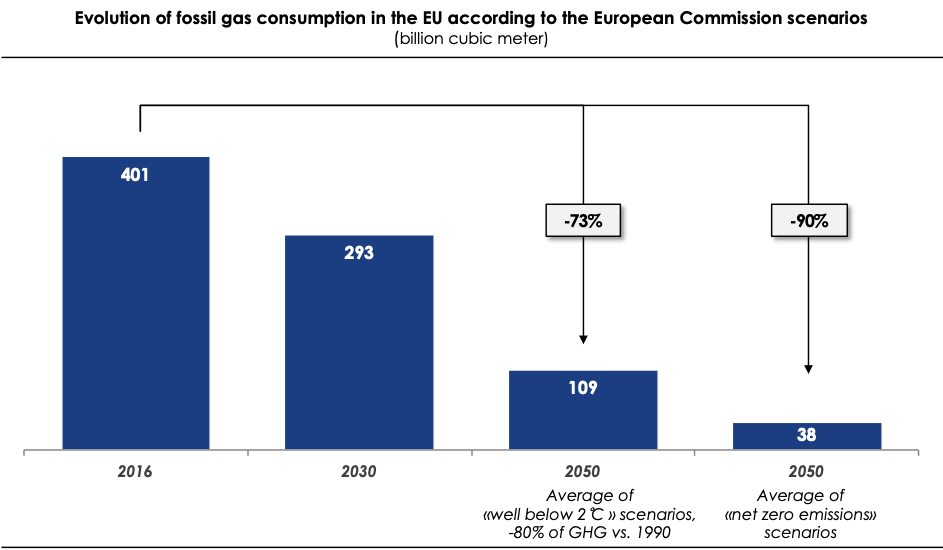

2. European fossil gas consumption is set to fall sharply if we set ourselves on an ambitious trajectory for reducing greenhouse emissions, for example a trajectory compatible with keeping global warming below the 2°C limit. In such a scenario, three effects combine with each other:

- European energy consumption decreases in absolute terms,

- the “gas” energy vector represents a decreasing part of the energy mix

- renewable gas replaces fossil gas. This reduction in consumption is described by the European Commission in its report A Clean Planet for All7, published at the end of 2018. The “well below 2°C” scenarios predict an average reduction in natural gas consumption by more than 70% in 2050 compared to their 2016 level, while the 1.5°C/zero net emission scenarios requires a reduction by about 90%.

Knowing that the EU is preparing to integrate a carbon neutrality objective into its legislation8, one can easily grasp how far we have yet to go to reach this objective, at least regarding fossil gas.

Source: European Commission, 2018

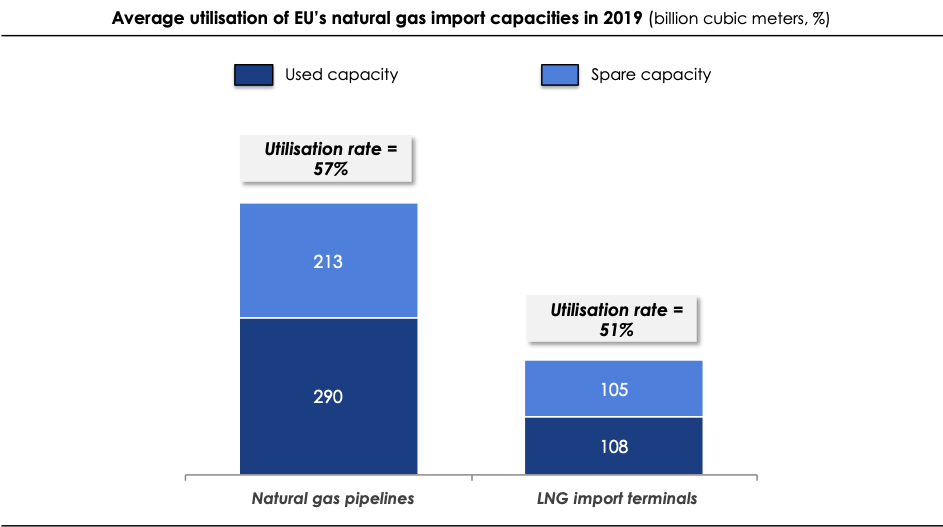

3. The EU's natural gas import capacity is already largely above its needs, with an average pipeline utilisation rate of 57% over 2019 and an average utilisation rate of 51% for LNG terminals. These overcapacities are not explained by the variation in consumption during the year: in 2019, the utilisation rate of LNG terminals peaked at around 65% in December, the annual average being 51%.

Sources : Commission européenne, 2018 ; M. Inman, 2020

Useless, dangerous and risky

Strictly speaking, investing in additional natural gas import capacity does not call into question the achievement of emission reduction targets. Indeed, it is possible to build new pipelines in order to diversify supplies, without these new networks being used at full capacity; in which case they would mainly have insurance value. At the same time, the gas flow entering the EU could be constant or even decreasing.

Still, these new capabilities open the door to imports larger than what they are today. The fact of making these imports possible represents in itself a danger for the achievement of European climate objectives, because the use that will be made of these facilities is not predictable over their lifetime (more than 50 years).

What about the insurance value? Indeed, if the investment in new natural gas import capacities is not justified:

- neither by the anticipation of an increase in European demand (it is expected to shrink in the next 30 years),

- nor by insufficient capacities to meet nowadays demand,

- nor by variation in inter-seasonal consumption.

This may then be justified by a concern for security of supply. This question has been examined in-depth by Artelys, at the behest of the European Climate Foundation. The results of their analysis are presented in a report entitled An updated analysis on gas supply security in the EU energy transition. After subjecting the EU supply-demand balance to several stress tests, the report concludes that: “The existing gas infrastructure in the EU is capable of meeting various scenarios for future gas demand in the EU, even in the event of extreme supply disruption”. Hence, given the expected evolution of demand, existing capacities do not need to be increased or diversified.

The report goes further: these investments are exposed to a now well-identified risk of losing value before the end of their economic life. This is all the more troublesome for the assets of the 4th list of Projects of Common Interest, which are likely to involve public funds.

The risk of seeing so-called « stranded » assets emerge has apparently not been taken seriously by European institutions. Does this mean that our ambitious climate targets themselves are not taken seriously by the majority of European decision-makers?

Note that an inquiry was opened in mid-February by the European mediator Emily O’Reilly, with the aim of examining the consideration of sustainability issues in the development of the 4th list of Projects of Common Interest by the Commission.

Conclusion

Financial actors face the crucial challenge of bringing infrastructure funding in line with climate objectives. In this respect, investing in projects that would allow additional imports of fossil gas into the European Union appears to be:

- useless, in light of existing capacities,

- dangerous for the respect of our greenhouse gas emissions reduction objectives,

- financially risky if the means to achieve these objectives were effectively implemented.

On the contrary, funding (and primarily public grants, loans and guarantees) should be channelled towards low-carbon projects, such as the development of biogas plants to produce biogas and local networks to connect these production sites.

Carbone 4 is working to provide decision-makers in the financial world, both private and public, with the tools to inform their investment decisions and their portfolio management strategies. Our 2 Infra Challenge methodology makes it possible to verify, for a given portfolio of infrastructure projects, that alignment with a 2° C trajectory is respected.

Sources :

- Inman, Gas at crossroads: why the EU should not continue to expand its gas infrastructure, 2020

- https://globalenergymonitor.org/tracker/

- 4th list of Projects of Common Interests : https://ec.europa.eu/energy/sites/ener/files/c_2019_7772_1_annex.pdf

- European Commission, A Clean Planet for all, A European strategic long-term vision for a prosperous, modern, competitive and climate neutral economy, 2018

- European Commission, Market Observatory for Energy, Quarterly report on European gas markets – Q4 2019

- Artelys, An updated analysis on gas supply security in the EU energy transition, 2020

Contact us

Contact us about any question you have about Carbone 4, or for a request for specific assistance.